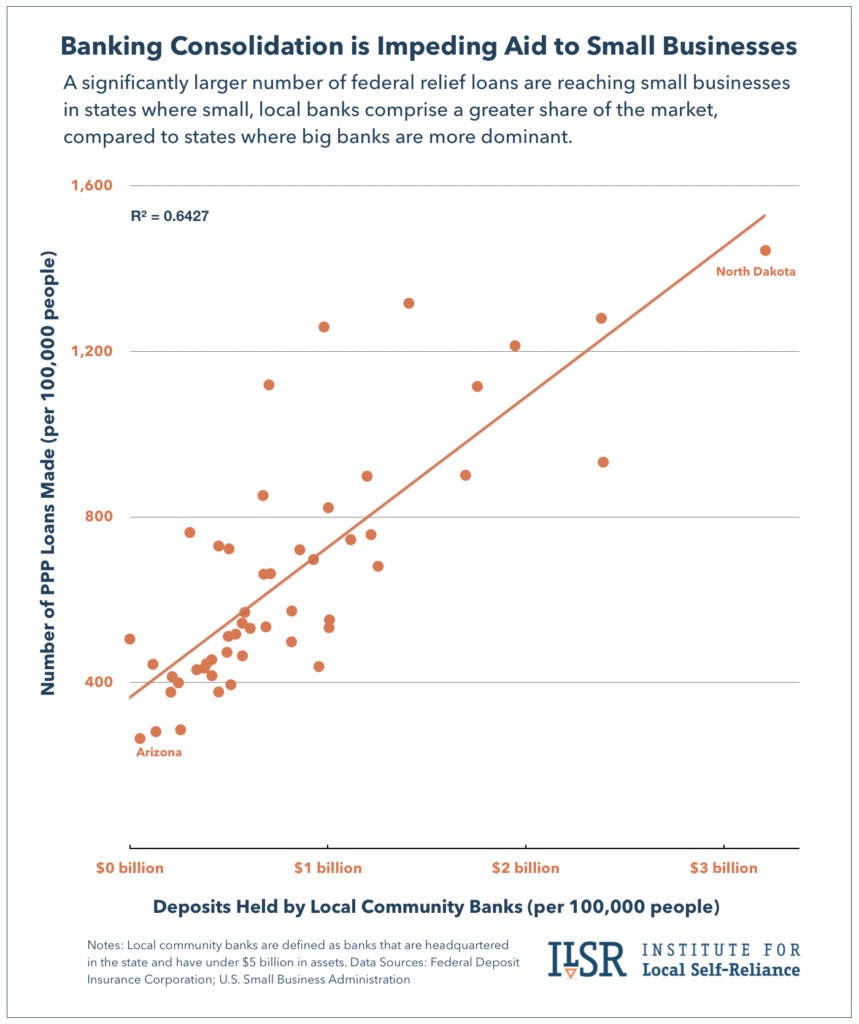

A significantly larger number of federal relief loans are reaching small businesses in states where small, local banks comprise a greater share of the market, compared to states where big banks are more dominant.

June 15, 2020 Update: PPP Loan Data Continues to Show that Big Bank Consolidation has Hampered Small Business Relief — Our most recent graph includes data from the second round of PPP funding.

During two weeks in early April, millions of small businesses scrambled to secure aid from the federal government’s emergency relief program. The Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) offered businesses shuttered by the pandemic a slender lifeline, delivered in the form of a forgivable loan that could be used to cover payroll and rent for two months. To get these loans out quickly, the U.S. Small Business Administration (SBA) deputized banks across the country to make them. But the rollout was chaotic and uneven. Some banks stepped up; others were mired in bureaucracy and confusion, leaving applicants in limbo. When the program ran through its initial $349 billion in funding just 14 days after launching, untold numbers of desperate small businesses — likely in the millions — had been left out.

Whether a business succeeded in getting a loan hinged to a significant degree on its location. Many more PPP loans were made in some states than in others (controlling for differences in population). What accounts for the difference? Our analysis found a strong correlation between the number of loans issued in a state and the relative strength of that state’s small local banks. As our graph shows, more loans were made in states where local community banks constitute a larger share of the market. By contrast, businesses located in places where the banking sector is dominated by big banks were much less likely to get relief.

States with a robust community banking sector will likely suffer fewer small business losses and less economic damage.

There is no fixed definition of a community bank.[1] For this analysis, we include banks that are headquartered in the state and have under $5 billion in assets. These banks account for just 13 percent of the banking market, as measured by their share of total banking assets.[2]

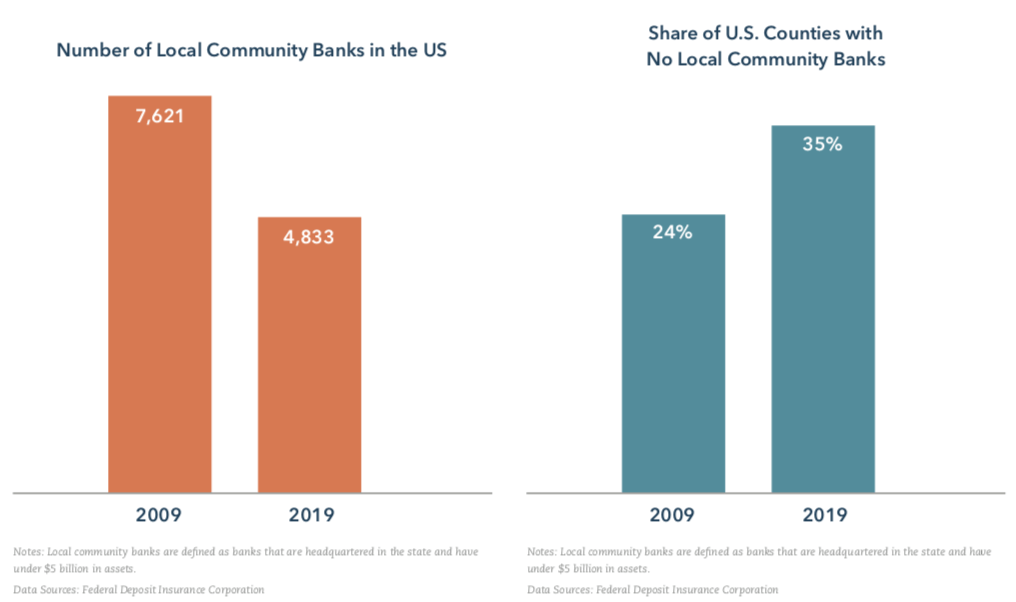

Our findings add to a large body of evidence that community banks outperform big banks by operating more efficiently and better meeting the financial needs of the real economy.[3] In particular, they provide a disproportionately large share of loans for new and growing businesses, in part because they’re better at accurately assessing risk.[4] Yet, federal banking policies continue to spur consolidation. Since 2009, the number of community banks has fallen by more than one-third, while a growing share of counties no longer have any local banks.[5]

What We Found

Drawing on data from the SBA and the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, we found that nearly three times as many PPP loans were made per capita in the ten states with most community banks per capita, compared to the ten states with the fewest. This relationship is even stronger when the measure is not the number of community banks, but rather their combined market share strength, as defined by the amount of deposits these institutions hold per 100,000 residents.

As our graph shows, North Dakota occupies one end of the spectrum. With nearly 10 community banks per 100,000 people, North Dakota has more of these local financial institutions than any other state, about six times the national average. These small banks account for about 80 percent of the state’s banking market, as measured by their share of deposits. Banks in North Dakota issued more than 11,000 PPP loans, or about 1,444 loans per 100,000 people.

At the other end of the spectrum is Arizona, a state dominated by big banks. Arizona has the fewest community banks per capita of any state, with just 0.2 institutions per 100,000 people. These banks account for only a small sliver of the state’s deposits. Altogether, just over 19,000 PPP loans were made in the state, or only about 265 loans per 100,000 people — five times fewer than in North Dakota.

For data on all 50 states, see the table at the end of the report.

In trying to explain these differences across states, some have suggested political corruption, noting that more loans were made in Republican- leaning states than in Democratic-leaning ones.[6] Others have pointed out that less urbanized states saw more lending.[7] But our analysis found that neither the share of GOP-leaning voters in a state nor the share of rural residents has more than a weak correlation with the number of PPP loans made. And even these links are likely to be more a function of the geography of banking consolidation than anything else. Big banks have focused on dominating big urban markets. As a result, large cities, which tend to have more Democratic voters, also tend to have more concentrated banking markets with fewer community banks.

Why Local Banks Succeeded and Big Banks Failed

By the time the PPP launched, Community Bank of the Bay in Oakland, Calif., had already moved 80 percent of its staff to the loan program. “We have no choice, there is no other business line. We invest in this community good times and bad,” the bank’s president, William Keller, told The Mercury News. Like all local financial institutions, the bank can prosper only if its community does. In two weeks, it made 175 PPP loans. The smallest was for $6,500.[8]

Union Bank & Trust in Lincoln, Neb., also got a jump-start, setting up an internal task force and writing new software to track applications even before the relief program launched.[9] The bank made PPP loans to more than 2,000 small businesses. Cortland Bank in Cortland, Ohio, had employees working double shifts to secure aid for 235 small businesses. “The last thing banks want to do, especially for loan customers, is see a business not be able to succeed,” the bank’s president said. [10]

“I kept seeing the stories about what a disaster [PPP] was on the national news and wondered what the difference was, and ultimately it comes down to is we were at a smaller local bank,” David Fields, co-owner of Wormtown Brewery in Worcester, Mass., told the Worcester Telegram & Gazette. The brewery has maintained payroll and health insurance for its staff thanks to a PPP loan from bankHometown, which processed 432 loans.[11]

Megabanks are too big to succeed at the very things we most need the financial sector to do.

By contrast, the nation’s biggest banks, weighed down by their own sprawling bureaucracies, proved unable to nimbly and quickly set up systems to process PPP loans. Citibank, for example, didn’t begin taking applications until one week after the program launched.business clients who maintain accounts of $25 million or more were first in line. JPMorgan Chase also favored its elite clients, ensuring that nearly all of its private banking customers who applied for a PPP loan got one. Among ordinary small businesses, only about one out of 15 who sought a loan from Chase succeeded.[12]

To some extent, these failures are a reflection of how little the megabanks pay attention to small businesses generally. In normal times, they don’t do much small business lending, in part because they aren’t very good at it. It’s a problem of scale. Unlike local banks, which are immersed in their communities and have a rich trove of “soft” information to draw from in assessing the likelihood that an entrepreneur will succeed in a particular market, big banks are operating at a scale that leaves them largely blind to information that can’t be quantified.[13] As a result, megabanks have higher default rates and make comparatively few of these loans.[14] The contrast is striking: Community banks provide 40 percent of small business lending, despite having only a 13 percent market share. Meanwhile, the top four banks — Bank of America, Citigroup, JP Morgan Chase, and Wells Fargo — control 41 percent of banking assets but supply just 16 percent of small business lending.[15]

We often talk about how megabanks are too big to fail. But the bigger problem is that megabanks are too big to succeed at the very things we most need the financial sector to do.

That was true before the pandemic, but now, in the face of an urgent crisis, it’s become even more of a handicap. Of the top four banks, JP Morgan Chase made the most PPP loans by far, but its volume, relative to its size, was only a fraction of that achieved by many community banks. Chase holds more than 12 percent of U.S. banking assets, but it accounted for only 1.6 percent of PPP loans and 4.1 percent of PPP loan dollars.[16] Had Chase matched the ratio of PPP loans to assets that the four community banks referenced above achieved, it would have made 36 times as many of these loans as it did.

Looking Ahead: Policy Responses & Economic Recovery

In the lead-up to the passage of the PPP, ILSR urged Congress to instead provide cash assistance to small businesses through direct payments from the U.S. Treasury.[17] This approach would have better met the urgency and scale of the crisis. (Indeed, it’s still needed given the continuing uncertainty.) That said, the PPP has provided a lifeline to some small businesses, thanks mainly to local community banks, which have managed to distribute these relief loans in spite of the SBA’s confusing rules and antiquated technology.

And yet, even though community banks have a track- record of better meeting the needs of small businesses, the SBA has been prioritizing big banks in how it operates the program. When the program launched, many community banks were unable to log in to the SBA’s portal to submit applications.[18] First National Bank of Osakis in Osakis, Minn., for example, had made SBA loans in the past, but this time was locked out of the system for more than a week before the agency fixed the problem. By the time the bank got in, the program’s funds were running out. “That gave us about 48 hours to serve as many of our customers that we could,” Justin Dahlheimer, the bank’s president, told us.

Congress has now authorized an additional $310 billion in funding for PPP loans. With this new round, the SBA is continuing to prioritize big lenders by allowing them to submit 5,000 loan applications in one bundle, while community banks are required to enter applications one-by- one through the agency’s slow and unstable online portal.[19]

Counties with a higher share of African American residents were more likely to see community banks shutter during this period.

This is part of a long-running pattern of marginalizing community banks as a matter of federal policy. In the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis, Congress bailed out the megabanks, in spite of their track-record of fraud, and yet allowed hundreds of local banks hurt by the ensuing recession to fail. At the same time, regulatory reforms did little to reduce the market power of big banks, while also imposing new compliance burdens on small financial institutions.[20]

As a result, over the last decade, the number of community banks nationwide has fallen by more than one-third, from 7,621 to 4,833. More than 35 percent of counties no longer have any community banks, up from 24 percent in 2009, we found. Counties with a higher share of African American residents were more likely to see community banks shutter during this period.[21] That may be one of the factors contributing to emerging evidence of stark racial disparities in PPP lending.[22]

As we look ahead, the erosion of the community bank sector will almost certainly continue to hamper our ability to respond effectively to the economic crisis. It will also impede recovery. States that have relatively few community banks will struggle to shore up existing businesses and finance new ones. All of this should prompt us to reconsider the wisdom of policies that foster banking concentration.

If you like this, be sure to sign up for the monthly Hometown Advantage newsletter for our latest reporting and research.

Endnotes

[1] FDIC Community Banking Study, Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, December 2012.

[2] ILSR analysis of bank data from the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation.

[3] “Implications of the ‘Volcker Rules’ for Financial Stability: Hearing Before the S. Comm. on Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs,” testimony of Simon Johnson, Ronald A. Kurtz Professor of Entrepreneurship, Sloan School of Management, Mass. Inst. of Tech, 2010; Dean Amel, Colleen Barnes, Fabio Panetta, and Carmelo Salleo, ‘‘Consolidation and Efficiency in the Financial Sector: A Review of the International Evidence,’’ Journal of Banking and Finance, 2004.

[4] “Banking for the Rest of Us,” Stacy Mitchell. Sojourners Magazine, April 2012.

[5] ILSR analysis of bank data from the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation.

[6] “Small Business Rescue Money Flowing to Major Trump Donors, Disclosures Show,” Lee Fang, The Intercept, April 24, 2020; “Bailout money bypasses hard-hit New York, California for North Dakota, Nebraska,” Aaron Glantz, Reveal, April 23, 2020.

[7] “Main Street bailout rewards U.S. restaurant chains, firms in rural states,” Andy Sullivan, Howard Schneider, Ann Saphir, Reuters, April 17, 2020.

[8] “For community banks and credit unions, coronavirus loans could be their big moment,” Leonardo Castaneda, The Mercury News, Apr. 21, 2020.

[9] “How a family-owned Nebraska bank became a leader on coronavirus loans,” Jeanne Whalen and Renae Merle, The Washington Post, Apr. 22, 2020.

[10] “Three Local Banks Disburse $447 in PPP Loans,” Josh Medore, The Business Journal, April 2020.

[11] “Paycheck Protection Program, community banks a ‘lifeline’ for Central Mass. businesses,” Cyrus Moulton, Worcester Telegram & Gazette, Apr 26, 2020.

[12] “Banks Give Richest Clients ‘Concierge Treatment’ for Pandemic Aid.” Emily Flitter and Stacy Cowler.” New York Times. April 2020.

[13] “Small Banks’ Competitors Loom Large,” Jeffery W. Gunther & Robert R. Moore, Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas, Jan./Feb. 2004

[14] ILSR analysis of bank data from the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation.

[15] ILSR analysis of bank data from the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation.

[16] “Biggest banks ‘prioritized’ larger clients for small business loans, lawsuits claim,” Stephen Gandel, CBS News, April 20, 2020; “Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) Report,” U.S. Small Business Administration, Apr. 16, 2020.

[17] “What the Federal Government Needs to Do to Enable Small Businesses to Survive the Coronavirus Crisis,” Institute for Local Self-Reliance, Mar. 19, 2020.

[18] “Press Release: ICBA and State Banking Associations Urge Paycheck Protection Program Changes,” Independent Community Bankers of America, Apr. 9, 2020.

[19] “Bankers Rebuke S.B.A. as Loan System Crashes in Flood of Applications,” The New York Times, Apr. 27, 2020.

[20] “One in Four Local Banks Has Vanished since 2008. Here’s What’s Causing the Decline and Why We Should Treat It as a National Crisis,” Stacy Mitchell, Institute for Local Self- Reliance, May 5, 2015.

[21] ILSR analysis of bank data from the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation.

[22] “’You’re Just Screwed’: Why Black-Owned Businesses Are Struggling to Get Coronavirus Relief Loans,” Kara Voght, Mother Jones, April 24, 2020; “Minority-owned small businesses could see relief in $484 billion aid package,” CBS News, April 22, 2020.